In one case, I found myself in a country in Latin America investigating a complicated persistent business compromise being implemented through both electronic and human means. I had already been working on the case for a few months and had narrowed down a list of insiders that we thought were conspiring with external entities.

I met with a trusted contact in the physical security department who had been allowing my team to access to the building at key times so that our team could perform disk and rudimentary memory acquisition.

I remember being surprised that the physical security department was being helpful. Admittedly, my experience had me thinking of the physical security departments in the U.S. with a staff that might be sleeping when no one was looking. To say I had low expectations is putting it mildly. Regardless, I made my inquiry.

The contact was briefed on the list of individuals on whom I hoped to gain information. He seemed eager to help and agreed that he and his team would apply some time to it and we would see what we could get. I assumed I would only get a few surveillance tapes from various building locations or at best, metadata on inbound and outbound calls.

Assumptions… well, we know what they say about assumptions…

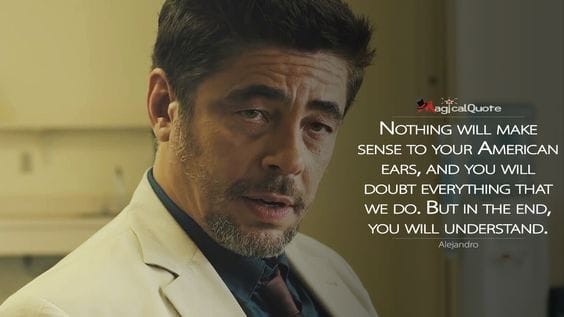

Two months later our contact scheduled a meeting about the findings of his department’s investigation. At this point I’d like to quote something from the film Sicario – a 2015 crime thriller about a high-principled FBI agent tasked with taking down the leader of a Mexican drug cartel:

Nothing makes sense to your American ears… but in the end you will understand.

This is EXACTLY how I felt as the investigator explained what he had found.

After going over significant findings, he shared an audio recording of one of the primary suspects. The recording captured a conversation that laid out the mechanics and risks of whole operation. Boom. Human mystery solved. I was left thinking about the technical artifacts.

Obtaining an audio recording wasn’t even on my radar. So not what a typical cyber investigator would ask for. And, so not legal in the United States.

But it made me realize that when working on investigations, don’t assume anything. Ask broad questions and let them come up with the information using the tools and rules you may have at your disposal. Look for new opportunities as well as new risks which may present themselves. My natural assumptions in this scenario had left me blind to asking for anything past physical surveillance, electronic media (data etc) and certainly did not include acquiring audio recordings of activity and conspiracy. As it turned out, someone was paying for these recordings to be done and this fellow had access to them.

So, lessons learned. Keep an open mind because some scenarios may yield opportunities you might not expect.

After more than year in Latin America, I started looking at different cases much differently based on risk, opportunity and the natural cultural fingerprint of a region.

Conclusions

On a high level my experiences lead to a number of broad stroke perceptions. For instance, applied in the scenario above, the source country falls more into a fear and power type identity versus a right identity. When asking for the information, the source applied the economics they usually operated in within that environment to achieve the goal.

In other scenarios, for instance in Asia, honor and shame based cultural norms make performing disk forensics or standard investigative practices much more sensitive in nature.

- Western Culture – Typical Optic, Right/Wrong; Black/White, Good/Evil

- Asian Culture – Typical Opic, Honor/Shame;

- Middle East – Honor/Shame

- Latin America/Northern Europe/Russia – Fear/Power

- The Old Country – …

Sociology has more insights into this, but starting every new investigation with the first lessons learned should be a requirement. You should always challenge the assumptions that are guiding the perspective in which you are viewing your investigation.